Hubble’s sharp vision has helped astronomers solve a number of mysteries about supermassive black holes, including their abundance and their influence on galaxies in the evolving universe.

Einstein’s theory of general relativity first described the characteristics of such hypothesized gravitationally collapsed objects. His theory described an event horizon swallowing light, which would prohibit telescopes from ever directly seeing such objects.

The actual term “black hole” wasn’t coined until six decades later by astrophysicist John Wheeler. In the early 1970s, the first black-hole candidate, Cygnus X-1, was discovered in X-rays coming from superheated material swirling around a black hole orbiting a normal star. The black hole is 15 times the mass of our Sun.

In the early 1990s, Hubble began to provide compelling circumstantial evidence for the existence of gargantuan black holes measuring millions or billions of times the mass of our Sun. Because of Hubble’s ability to discern faint objects in the vicinity of bright objects, the telescope made definitive observations showing that quasars (very distant, compact sources of intense radiation) dwell in the cores of galaxies. These galaxies are greatly outshined by the quasar’s “floodlight-beam” brilliance. Hubble revealed that most of the galaxies were seen in the process of colliding with other galaxies, and, according to theory, these violent encounters would fuel a central black hole. Engorged with gas, the black hole loses some material to blazing jets that shoot out of a galaxy’s center like a blowtorch, which are easily resolved by Hubble.

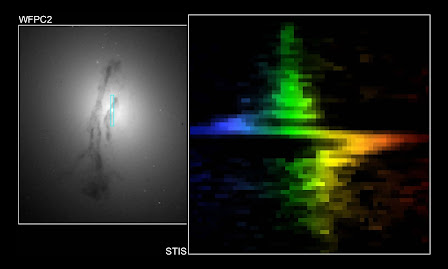

Next, Hubble greatly bolstered the idea of supermassive black holes by measuring their masses, providing the first observational measurements that proved their existence. In 1997, Hubble astronomers looked at the nearest “mini-quasar,” the brilliant core of the giant elliptical galaxy M87. Astronomers used spectroscopy (dividing starlight into its component colors) to “weigh” a black hole to see if the amount of its unseen mass far exceeded the mass that could be attributed to stars alone. Hubble’s spectrograph measured the speed of gas trapped in the gravitational field of a black hole at the center. The extreme velocities indicated the presence of an ultra-compact central mass that could only be explained as a black hole.

The Hubble image on the left shows the core of the galaxy where the suspected black hole dwells. Astronomers mapped the motions of gas entrapped in the black hole’s powerful gravitational pull. The change in wavelength, or color, records whether an object is moving toward or away from the observer. The larger the excursion from the centerline—seen as a green and yellow along the center strip—the greater the rotational velocity. If no black hole were present, the line would be nearly vertical across the scan.Astronomers used Hubble to measure the velocities at which stars and gas swirl around a black hole, to catalog black holes in active and quiescent galaxies. A Hubble census of galaxies showed that supermassive black holes are commonly found in a galaxy’s center. The survey suggests that black holes may have been intimately linked to the birth and evolution of galaxies. This idea is bolstered by a relationship, developed by Hubble observations, that a black hole’s mass is tied to the mass of a galaxy's central bulge of stars. The more massive the bulge, the more massive the black hole. This relationship implies there is some feedback mechanism between the growth of a galaxy and its central black hole.